Heceta Head Lighthouse

92072 Highway 101, Yachats, OR 97498

Let's Get the Ghost Story Out of The Way, Shall We?

I was a naturalist for the Forest Service in the 1990s and worked at Heceta Head. When there I could tell people stories about all the keepers and their families who lived and worked at there, I could explain how a Fresnel lens worked, and I could list every fact, figure, and date that had any relevance to Heceta, but the thing most people asked about was the ghost story. I told them that I was paid to tell them the facts for free, but that fiction would cost them a 25¢ donation.

I'm hoping you'll read some of the true stuff about Heceta, but if you want to skip ahead and get straight to the ghost story, click here.

Stuff other than Ghost Stories about Heceta Light House

In the mid-1800s, ports and lighthouses were springing up along the west coast, but the government ignored the Siuslaw River. Even an 1851 survey map showed no river existing between the Umpqua and the Alsea. Finally, in 1889, Congress allocated $80,000 for the construction of a lighthouse at Heceta Head.

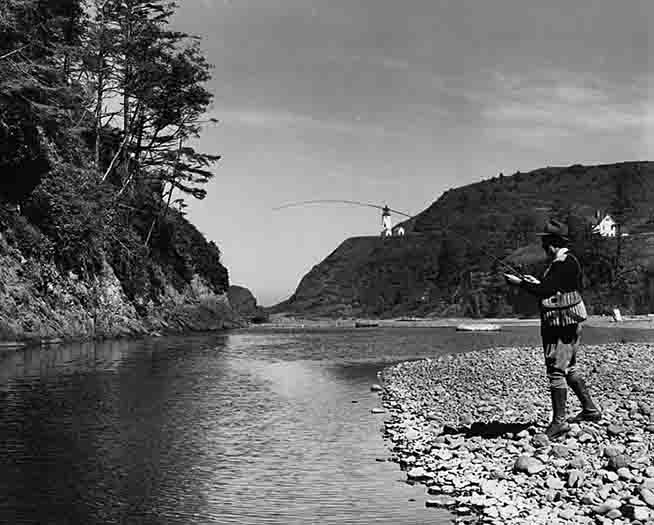

Much of the lumber used in construction came from Florence and Mapleton and was allowed to float to shore after being thrown overboard near Cape Creek Beach. They didn't employ the same method to transport the 640 prisms for the lens. Surf boats were used, a technique only slightly less precarious than having the fragile items thrown directly into the ocean. The first-order Fresnel lens and brass clockworks were valued at $12,000, the same as the rest of the 205 foot (63 m) tower. Thousands of barrels of powder used to grade the site were transported over the mountains in wagons as the steamer's license did not permit it to carry explosives.

The five-wick lamp was finally lit on March 30, 1894, and generated 80,000 candlepower. It used 2,500 gallons (9,500 liters) of coal oil a year. In 1934 a one million candle power electric bulb was installed. In 1963 the lighthouse was automated. Today it is the most powerful marine light on the Oregon Coast and can be seen 21 miles (34 km) out to sea.

Light House Keeping was not Light House Keeping

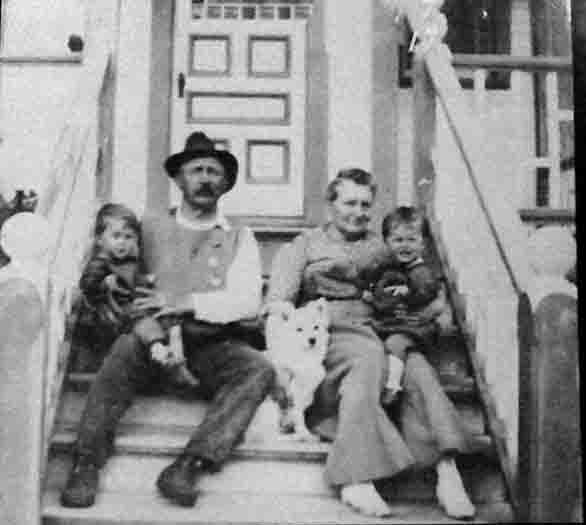

The first head keeper at Heceta, Andrew P.C. Hald, earned $800 per year. The salary was fixed in 1867, and not increased for 50 years. They really believed in pay freezes back then.

Lists and lists of instructions were given to lighthouse keepers. "The light-house shall be lighted and the lights exhibited for the benefit of mariners punctually at sunset daily...During each entire night, from sunset to sunrise... during thick and stormy weather those keepers who have no assistants must watch the light during the entire night." The clockworks that powered the revolving lens had to be wound manually every four hours.

There's more to being a lighthouse keeper than keeping the light on, though. Those not working the midnight to sunrise shift started their cleaning duties at 9:00 am. Lighthouse inspectors would make surprise visits at least once a year. The glass and brass had to be polished. The whole interior of the lighthouse lantern was frequently repainted white and kept clean and free from soot and grease. The instructions said that flat brushes were to be used for sashes and varnishing, and for painting in lines or narrow spaces. When the bristles of a brush got loose, they were instructed to drive a few thin wedges of wood inside of the binding twine or thread, which would "render them whole and fast again."

The inspectors even checked over the keeper's house, poking their noses into cupboards and sometimes donning white gloves and running their fingers atop sills and doors. The head lighthouse keeper had a bit more cleaning to do than his assistants. His house's chandelier had six bulbs while the first assistant's had five, and the second assistant had to make do with four.

A Beached Whale at Heceta

Frank DeRoy, a first assistant lighthouse keeper at Heceta in the early 1900s knew exactly what to do when a dead whale washed ashore in the early have his wife, Jenny, take a photo of him standing on top of it posing muscle-man style.

Several days later second assistant Overton Dowell's girl friend, Mary Hefty, came for a visit from Florence. Traveling the thirteen miles between Florence and Heceta Head in those days was no easy task. The highway at the time was the beach. Where there was no beach, you had to go inland through dense forest. If you drove, which few did, you carried with you the same things I'm sure you carry in your trunk today: saws, axes, dynamite.

Mary walked the whole way. They were hardier back then. Plus she was in love. She arrived as beautiful as ever. Overton borrowed Frank's camera to take a picture of her. Then he had the brilliant idea of taking a picture of her standing on the whale. She was in love, but she wasn't stupid and said, "No."

She did agree to take his picture. Overton wanted to replicate Frank's stunt and posed muscle-man style on top of the whale while Mary struggled to figure out how to use the camera. It was not a point and shoot. It was a heavy-view camera on a tripod where the image was upside down. Mary had never used a camera before. "Hurry up, sweetie," Overton said just before sinking into the whale.

Or at any rate that was the way the story was told for decades.

In 1997 the Forest Service had a Passport in Time (PIT) project conducting oral histories with people who had either lived at Heceta or had some connection to it.

Frances Dowell, Overton Dowell's, daughter-in-law said in one of those interviews that not only were Overton and Mary married at the time, but that Mary was also six months pregnant. Frances said she thought a photo had been taken of him standing on the whale in his uniform along with some of the daughters of the head keeper, Olaf Hansen, but she didn't think he fell into the whale. She probably doesn't believe there's a ghost there either.

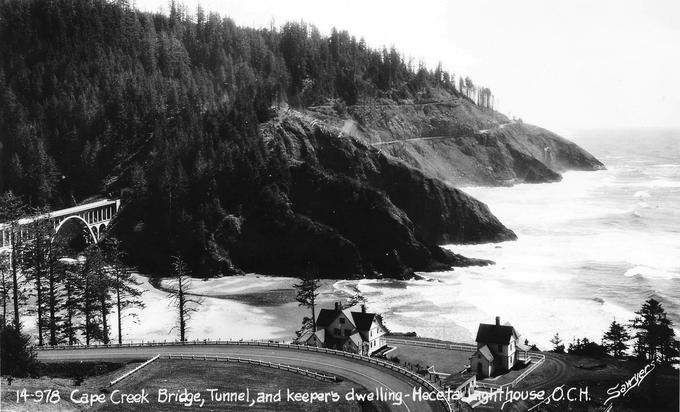

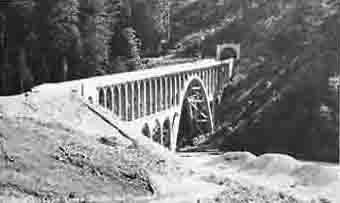

Cape Creek Bridge and Tunnel

"Honey, let's go watch some highway construction," is not something you'd probably hear today. But when they were building the Cape Creek Bridgeand Tunnel in 1931, that's what people did. Much to the annoyance of truckers trying to make their way to the site.

Ninety men simultaneously working on the bridge's graceful vast arches, all using noisy tools, power saws, rock crushers, and the like, was something to see, if not hear.

The Siuslaw Oar, a Florence paper, questioned Oregon's wisdom of putting "an architectural beauty which could adorn the metropolis of Paris" over a knee-deep creek in the middle of nowhere.

The bridge's designer, Conde McCullough, however, believed that just because something was functional didn't mean it shouldn't also be beautiful.

Unfortunately, by the 1980s, the bridge was crumbling. Some sand used in the concrete came from the beach contained salt that caused the rebar to rust. In 1991 they cathodically protected the bridge, not to be confused with Catholic protection where you just pray the bridge won't fall down. They stripped the bridge down and coated the rebar with zinc. This essentially turned the bridge into a 1.5-volt battery. Two bridges and you can power a TV remote.

In 1999 a rockslide between Heceta and Sea Lion Caves blocked the highway for 99 days. The nearest paved road parallel to Highway 101 is I5. That meant that unless you were willing to take a poorly maintained and barely marked dirt road, you had to take a 182-mile detour to get to Florence from Yachats.

Heceta's Name Sake

Heceta Head was named after Don Bruno de Heceta, a Portuguese who explored much of the Northwest coast. In 1775, sailing in secrecy for the Royal Navy of Spain he was ordered to "...land often, take possession, erect a cross and plant a bottle containing a record of the act of possession." At about 46 degrees north latitude, Heceta wrote of a large bay discharging a current so strong it drove his ships out to see. He said it might be "the mouth of some great river or of some passage to another sea." He'd seen the Columbia River and but didn't know it . He continued on because his crew was "much fatigued by the violence of the weather."

What You've Been Waiting For: Heceta's Ghost Stories

When Jim Alexander and his crew were doing repairs on the house in 1975, tools were always going AWOL. Some eventually turned up, but not anywhere near where they had been lost. Some were found in the garage, some were neatly stacked on the porch.

In a manner Alexander described as being like something out of an Abbot and Costello movie, a couple of workmen broke an attic window while moving a ladder. When Alexander went to fix it, a punching bag hung from the ceiling, and morning sunlight poured through the windows of the dusty attic.

"I had a black stocking cap on and it felt like it came clear up off the back of my head," Alexander said in an interview. "I just freaked out. I was looking at that glass and I knew there was somebody back there behind me. My hair was just straight-up--like I was electrified. And I turned around and there she was. She was just standin' there, askew--at an angle in the air. This old woman was standing there. Her gown looked like she was standing against the wind, and her feet was off the ground about a foot. She was physically floating, and the wind was blowing her chiffon gray gown."

Alexander said the woman, her arms outstretched, was between him and the attic's only exit--a trap door. The ladder to the attic is steep, and the top rung is three or four feet below the trap door.

'I took a step back against the wall," Alexander said. "I had to go past her to get down, and she's still comin', comin' comin' comin'.'" As she got closer, close enough to where he was just about ready to touch her, she started turning transparent and then went right through him.

"I just wheeled, and I baled out--just dove down the ladder--almost broke my shoulder," Alexander said.

It took several days for Alexander to build up enough courage to go back to Heceta. While there, he accidentally broke yet another attic window, this time with a hammer. He replaced it from the outside. Since he had vowed to never enter the attic again, he left broken glass scattered about the floor.

At about 2:00 am the next morning Harry and Anne Tammen, the house's caretakers, were awakened by scraping sounds coming from the attic. When they went upstairs, they found the glass from Alexander's broken window swept into a neat pile.

Harry and Anne went about very scientifically to learn the identity of this anal retentive ghost with kleptomaniac like tendencies: they used a Ouija board with a plastic "Made in Taiwan" planchette (the doohickey that the spirits supposedly move).

It spelled out R-U-E

They speculated that Rue was either a mother looking for her child, or a child looking for her mother.

The first lighthouse keeper, Albert Peter Cornelius Hald's baby daughter died at Heceta Head. The baby's death was due to scarlet fever, or to some other common childhood illness say some sources; or drowning in either a cistern or the ocean, say others. The baby is believed to be buried somewhere on the station grounds, but much of the area is covered with blackberry bushes, and nobody today can find a grave there.

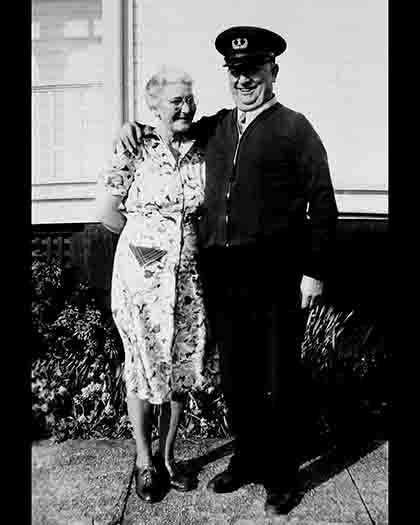

For years Harry delighted in telling people stories about the ghost, but eventually, he tired of it. In 1994 a reporter called him in Florida where he an Anne then lived, and Harry said, "I'm just a crotchety old man. I moved 3,000 miles to get away from the damned ghost."

Heceta's ghost gained national fame in 1980 when Life magazine included it in an article titled Terrifying Tales of 9 Haunted Houses. Consequently, Rue gained the type of credibility that is acquired by virtue of being written about in a respected magazine.

In 1982 a CBS movie-of-the-week The Fog was filmed at Heceta House, enhancing its ghostly reputation. In the movie's opening scene, a morning after a fierce storm, a boy wanders along the beach at Devil's Elbow looking for seashells. Suddenly, he sees something at the high-tide line and walks toward it. As he draws near the spot, he drops to his knees and clamps his hands to his face. The camera pulls back to reveal the boy's grandparents buried up to their chins in the sand. The boy screams. The movie goes downhill from there. Fred Rothenberg, a movie critic for the Associated Press, told his readers to watch "something else" that night.

I will confess that the first time I went into Heceta's attic I let out a shriek. Then I started laughing. What had startled me was not a ghost, but an old resuscitate-Annie dressed in a plaid dress and a hat that hung from the rafters.

I will confess that the first time I went into Heceta's attic I let out a shriek. Then I started laughing. What had startled me was not a ghost, but an old resuscitate-Annie dressed in a plaid dress and a hat that hung from the rafters.

My own personal theory about Rue is that if she really does exist, what she was trying to spell out on the Ouija board was not R-U-E, but R-U-D-E. After all, a man breaks not one, but two windows in her house, goes without cleaning up the mess, and then has the gall to accuse her of stealing his tools.

But Wait, There's More

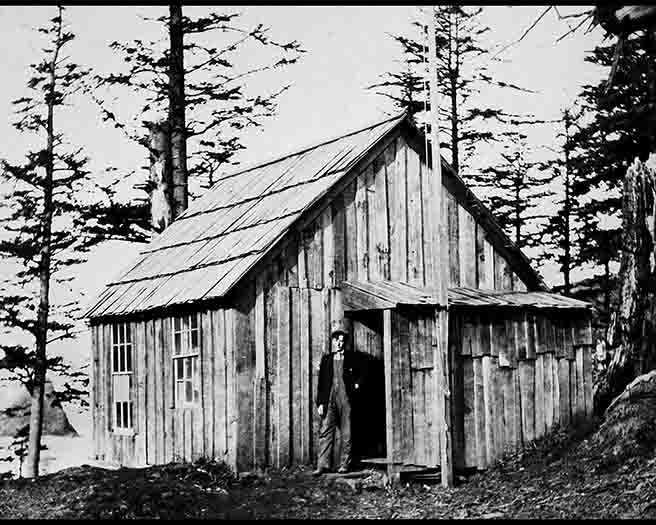

Through a quirk of history the U.S. Forest Service ended up owning the house. By the 1990s the almost 100-year-old building was in pretty bad shape. I was part of the team tasked researching its history and with restoring it.

It was an era of no new taxes, so to keep the structure standing we had to figure out a way of making it financially self-sustaining. The community was invited to offer suggestions. Many of their suggestions started with the letter B: turn it into a brewery, turn it into a bed and breakfast, or turn it into a brothel. The last one would probably have brought in the most money, but we opted for B&B. We were the U. S. Forest Service, after all.

Mike and Carol Korgan were the first ones to run the B&B. When the Forest Service interviewed them for the position, they were asked in jest how they felt about living in a house rumored to be haunted. "No problem," they said. "In fact, would you mind if we brought our own ghost?"

You could have heard a ghosts' dress rustle in the ensuing silence. The Korgans explained that they had lived in a house in Portland built by a man who lost ownership of it during the depression. He was so despondent that he hanged himself in the attic.

John haunted the house while they lived there but certainly was a benevolent soul. Once when their daughter Michelle was very young the house caught on fire. She said she was led to safety by a man, who the Korgans assumed was the ghost, John.

When they moved from the house, the Korgans discovered it wasn't the house that was haunted, but a couch they took with them. The couch is nine-feet-long, too long for most storage lockers, so they wanted to bring it with them.

I told them that although they'd be running the B&B it was still owned by the U. S. Forest Service and was considered a national cultural resource. If Rue existed, she was a Federal ghost. "Consequently," I said, "I'm pretty sure the Forest Archaeologist, Phyllis Steeves, wouldn't sign off on this unless you agree that if there were any problems between the two ghosts, John will have to leave."

According to Mike, Rue and John got along fabulously and he often heard them at night making "wild whoopee." Who knows. Maybe Heceta now has little ghostlettes.

***

This website, yachats-history.com, is a work in progress. More stories coming soon.