The Siletz Reservation 1855-1956

In 1843, 1,000 persons traveled from Independence, Missouri, to the Willamette Valley--1,900 miles--in the "Great Migration." By August 13, 1848, when Congress passed the bill creating the Oregon Territory, 10,000 Euro-Americans were already living in Oregon.

The pioneers came for many reasons, but most came because there was the promise of land--free land that was fertile beyond belief.

In 1843, Peter Burnett, later governor of California, said with a twinkle in his eye: "Gentlemen they do say, that out in Oregon the pigs are running about under the great acorn trees, round and fat, and already cooked, with knives and forks sticking in them so that you can cut off a slice whenever you are hungry."

There was one big hitch, though--Oregon still belonged to the Indians. In July 1849 the Oregon Territorial legislature endorsed a "memorial" that urged the Indians "early removal from those portions of the territory needed for settlement, and their location in some district or country where their wretched and unhappy condition may be ameliorated." Arid Oregon, east of the Cascades, was considered the ideal location--by the Euro-Americans.

In 1850 Congress set up a commission to negotiate treaties with the various Indian groups in Oregon. Congress passed a law that the Indians had to sign treaties agreeing to cede--give up--their homelands before settlers could get title to them. In April and May, the commissioners held treaty councils at Champoeg. Feasting on oysters, canned strawberries, and champagne, and talking about the "Great White Father in Washington," the commissioners tried to convince the Indians to give up their land and move. Most refused. By the time the commissioners used up the $20,000 appropriated for their mission, only six treaties had been negotiated, and no Indians agreed to move east of the Cascades.

It didn't matter. The Senate wasn't going to to ratify the treaties anyway. The commissioners didn't have authority to negotiate treaties. Without their knowledge, Congress had stripped them of their powers even before they reached the territory. Furthermore, on September 27, 1850, Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Act--a law that authorized the government to give away hundreds of thousands of acres of Indian land to settlers. This Act granted 640 acres to couples--white men and women, "American half-breed Indians," and immigrants who had filed for naturalization, living in Oregon at the time--and 320 acres to single men. The Rogue War started in 1852, and was one of the few instances of violence between settlers and Indians, much of it spawned by Gold Fever. The Rogue River Tribe (the Takelma) and the Takelman-speaking Cow Creek Band of the Umpqua were often attacked by vigilantes avenging alleged wrongs. One Martin Angel rode into Jacksonville yelling: "Nits breed lice. . . . We have been killing Indians in the Valley all day. . . . Exterminate the whole race." A mob formed and hanged a seven-year-old Indian boy.

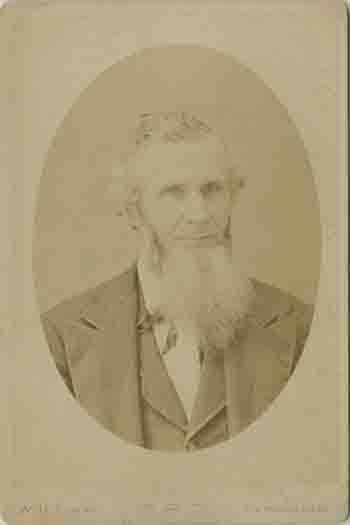

Joel Palmer, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, negotiated treaties with these two tribes in 1854. They were the first treaties in Oregon actually to be ratified by Congress. The Rogue River Indians ceded hundreds of square miles of land to the United States for about 2.3 cents an acre.

Soon all of the Indians of western Oregon, whose aboriginal territories included all of the lands and waters between the Columbia River and the Klamath River, and from the summit of the Cascade range to the ocean, signed treaties ceding their lands--twenty million acres in all--in exchange for a permanent reservation. Congress didn't ratify most of the treaties, but the government acted as if Congress had.

On November 9, 1855, President Franklin Pierce signed an Executive Order creating the Coast Reservation, later known as the Siletz Reservation. The reservation, 1,382,400 acres, including Heceta Head, extended north and south about 100 miles, from Cape Lookout to Tahkenitch Lake, and inland about twenty miles. The land was closed to non-Indian settlement. It was assumed that the land was so undesirable that no Euro-Americans would want to settle there.

At the time the region was only partially explored and thought to be worthless. In 1852 Cyrus Olney, writing for the Oregon Statesman, said of it: "We saw nothing in the country or its productions and resources sufficiently attractive to induce an immediate settlement of it, in the face of all its disadvantages such as limited quantity of good land, its destitution of timber and grass and its want of facilities for communication with the rest of the world."

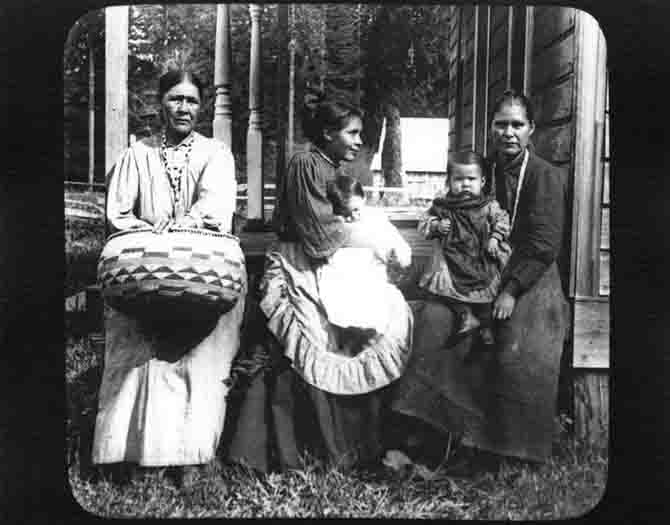

In January and February of 1856, some Indians were marched 200 miles through the snow to the reservation, while others were brought in by steamboat. Each Indian was allowed to bring one pack. Most people filled their packs with food. One said: "We left behind many fine canoes, homes, tanned hides and other belongings found in an Indian colony at that time. We were all heartsick."

In the first year on the reservation, several hundred died from exposure, starvation, and disease. In 1857 Robert Metcalfe, an Indian Agent, said the more sensitive died from a "depression of spirits."

By 1859 about 100 shamans had been killed for failing to cure the diseases that ran rampant on the reservation. Patty Whereat, a linguist of Coos and Hanis languages, said that being a shaman "was a dangerous profession. They might kill you to break the 'evil.'"

Dr. John Milhau served as U. S. Army surgeon at Fort Umpqua on the North Spit at the Umpqua's mouth from 1856 to 1857. He wrote George Gibbs, a linguist and ethnographer: "[The Indians] state that within the last twenty years, a great many have died along to coast of the 'Doctor's sickness.' Their idea of the disease is that the medicine man or woman wishing to destroy an individual performs certain incantations, upon which a small insect with a very hard shell and numerous legs, penetrates into the vitals of the victim and feeding upon the tissues increases in size, while the sufferer loses all appetite, coughs, becomes emaciated and dies."

Don Whereat, former historian for the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indianssaid: "One of the biggest problems in the early days [of the reservation] was fighting amongst themselves, because you had tribes that had hated each other for generations all put together." Over twenty tribes were on the Siletz Reservation. Some spoke languages as different from one another as English is from Finnish. In Western Oregon, there were eight language families, and some of these families had six or eight different dialects. Those that had traded before often communicated via Chinook jargon, a trading language that has been referred to as Northwest Esperanto.

Conflicts also arose between those who had ratified treaties and those who hadn't. In 1865 the Indian Agent spent $46.23 per Indian for the 121 who had ratified treaties, and only $2.50 per Indian for the 1,824 whose treaties hadn't been ratified.

In 1859 the Alsea subagency was established in Yachats. It administered the affairs of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, Siuslaw, and Alsea Indians.

The Siletz Reservation was created at a time when the government was trying to "civilize" Indians. "Civilized" people were Christians who spoke English, wore cotton or wool clothing--and tilled the soil. The mission of the Indian Agency at Siletz was to turn very successful fisher-folk into farmers on land selected to be a reservation because it did not have good farmland. The first years were disasters.

The Indians were used to digging and eating roots--camas, fern, and skunk cabbage. They weren't used to having to wait for the roots to develop into crops, and thus the first year, they lost most of the potatoes.

Once a hundred Indians had to haul flour on their backs, walking over thirty-five miles on a rugged mountain trail to the reservation. And the flour only made the Indians sick. The government had paid $20 a barrel for "good quality." What they got were "shorts and sweeps"--meant for cattle feed. Part of the reason for the bad flour was that the government had a hard time finding suppliers because they never paid for things up front. Everything had to be bought on credit.

Transportation costs often exceeded the cost of supplies because the reservation was so inaccessible . A barrel of flour that cost four dollars at the mill cost thirteen dollars to ship to Siletz.

Many of the Indian Agency employees weren't much happier than the Indians. Most hated the climate and social atmosphere. H. R. Dunbar, a teacher on the reservation in 1867, viewed the place as a "God-forsaken region" of floods, foul weather, loneliness, and personality conflicts. He wrote: "No one that thinks anything of his family and that has never stepped in such a hole as this with his family absent from him, can realize what it is to stop in this lonesome, wicked place."

Education was compulsory on all reservations, but the rule was not enforced because some schools were so inadequate. When former Army Captain J. B. Clark and his wife arrived to teach school at Siletz in 1863, the building was so decrepit that it was used to house livestock. The Clarks developed a "manual-labor" boarding-school. Besides the three Rs, pupils were taught "morals, manners, and hygiene." The boys also worked with Mr. Clark in planting a garden and learning various vocational trades, including carpentry and horseshoeing. Mrs. Clark taught the girls "housewifery--cooking, sewing, knitting, and general homemaking. At the time, these pupils were among the best educated in the state, Indian or non-Indian.

The pupils, most of whom were under twelve, seemed to like the school. The parents did not. The children were not living with them, and they were not learning their native languages and customs. Intertribal marriages were also causing a loss of culture.

In 1864 something of value to Euro-Americans was found in Yaquina Bay: marketable rock oysters (Pododesmus macroschisma). In 1864 a schooner, the Cornelia Terry from the Solomon, Dodge and Ludlow & Company, started harvesting the mollusks. Indian Agent Ben Simpson stated that the Indians should share in any profits since the government treaty had granted the Indians rights to monies made from reservation lands. The schooner's commander, Captain Hillyer, claimed he had a free right to fish in American waters because he had been issued a coasting license in San Francisco.

Another San Francisco oyster firm, Winant & Company, agreed to lease the beds and pay 15 cents per bushel. Hillyer, however, continued to harvest oysters and gave no payment to the Indians. He was arrested, detained for twelve hours, and filed suit against the government, claiming that he had been treated unjustly.

Eventually, the court ruled against Hillyer, stating that since the government had the right to establish a reservation, it also had the right to decide how the land should be used. It was a small victory for the Indians.

What little ground they had gained was lost by all the publicity generated by the case. Settlers began hearing about the region and wanted to move in. Agent Simpson claimed that "unless something is done soon it will be impossible to prevent trespass upon that portion of the reservation unless a strong military force be kept on the grounds." The government appropriated $16,500 to purchase Yaquina Bay from the Coos, Siuslaw, Alsea, and lower Umpqua tribes and remove them from the area.

The government opened up Yaquina Bay to settlement. Alsea Agent Collins told the Indians living there that they would be provided for at Siletz. They didn't believe him. They said: "We gave up our former homes and lands; we are assured this should be our permanent and lasting habitation. Here we have erected comfortable houses; our land is just being put in such a condition that we may live comfortably; we are growing old and are not able to till new fields or erect new homes; and more than this, we have always lived by the coast--been used to subsisting on fish and game and to remove us to the interior we must die."

Speculators and settlers moved into the Yaquina Bay area before all of the Indians had been moved out. In George Collins's annual report, he wrote of one example: "'A' walked into Coquille John's hut on Coquille Point, informed him with the untutored mind that the land belonged to the whites, hustled the Indians out and seated himself on a soap box by the fire. In less than an hour 'B' arrived on the scene, gave 'A' eighty dollars for his claim. 'A' jumped into his canoe and quickly had another claim."

On March 3, 1875, Congress "officially" established the Siletz Reservation as a permanent home for Indians whose treaties hadn't been ratified. Settlers kept moving into the area, so the Alsea Agency was abolished, reducing the reservation to 223,000 acres between Cascade Head and Cape Foulweather.

Indians had the option of moving to what was left of the reservation or resettling along the coast. Those who chose to move to the reservation were to be provided for and could receive allotments. Most chose not to move to the reservation. Some, including many Siuslaw Indians, returned to the lands they or their families had come from twenty years earlier.

The General Allotment Act of 1887, also known as the Dawes Act, broke up the communal ownership of the reservation and encouraged the acceptance of European concepts of property ownership. The Allotment Act required land to be surveyed so that 80-acre homesteads could be assigned to individual Indians. The Indian Agents tried to help the Indians make good selections, but competition for prime pieces of land sometimes pitted family members against one another. Powerful individuals obtained cleared, fenced, improved lands. Others received land that was inaccessible or densely forested or lacked water.

Once all the Indians had been assigned a homestead, the rest of the reservation's land was declared "surplus." On October 31, 1892, the government bought the "surplus" lands--192,000 acres for $142,000. The subsequent scramble for ownership of these lands, some highly valuable, became part of the widespread land frauds of the era. S. A. D. Puter, "King of the Oregon Land Fraud Ring," wrote Looters of the Public Domain from a jail cell. One chapter was titled:" How the Indians were Robbed of Their Homes for the Benefit of Pale-Faced Looters, Under the Guise of Treaty Rights."

In 1929 the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw obtained an act from Congress that let them file a lawsuit on the grounds that their land had been appropriated without compensation or a ratified treaty. After the tribes worked twelve years to bring suit, the judge said, ironically, that since they had been a relatively peaceful people, it was difficult to establish with any certainty their location before 1855. In 1938 the court ruled that the tribes had no "right, claim, or title to any part of the coast of Oregon whatsoever," and the Supreme Court denied an appeal.

In 1954 Congress held hearings on whether or not the Indian Tribes should be "terminated": by a stroke of the pen, Indians would no longer be considered Indians. If they weren't Indians, they wouldn't be entitled to anything promised, by treaty, to Indians.

In February Orme Lewis said before a congressional committee: "It is our belief that the Indians subjected to the proposed bill no longer require special assistance from the Federal Government, and that they have sufficient skill and ability to manage their own affairs. Through long association and intermarriage with their white neighbors, education in public schools, employment in gainful occupations in order to obtain a livelihood, and dependence on public institutions for public services, the Indians have largely been integrated into the white society where they are accepted without discrimination."

In 1956 Congress terminated every tribe and band west of the Cascades and the Klamath in south-central Oregon. Don Whereat said this ended what few benefits they had, which by then weren't many. Whereat lived in Coquille, Oregon, and he said that, even before terminating, "if you had to go to the hospital, you had to go to the hospital in Tacoma, Washington."

Describing being an Indian at the time, Whereat said: "I was pretty young then. . . . I was a member of the Indian tribe, but you know it really had no meaning for me at the time. . . . I knew who I was, but it just wasn't talked about. And I had a fascination with the Indians. . . . I don't know if it was a kind of love-hate relationship or what, but frankly I was scared to death of Indians . . . of my own family, some of the things I heard about, and I was like everybody else. I would go to the movies and root for the cowboys and soldiers over the Indians."

In the 1970s, the Red Power Movement and the American Indian Movement led by a new generation of Indian leaders, many college-educated and supported by able legal assistance, called for correcting the problems of termination. In 1977 Congress passed a bill restoring Confederated Tribes of Siletz to "recognized" status. The Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw were restored to that status in 1984.